|

By Jack Harte

When some friends of mine decided to set up Scotus Press, one of the writers they wanted to publish was Michael Phillips and they asked my assistance in tracking him down and procuring his work.

They remembered the stories of his that were published in various magazines and anthologies back in the 70’s. It was no surprise they remembered them – anyone who read them couldn’t forget. I remembered too – they were quite extraordinary stories, bizarre, among the most original and witty, with a Beckettian disdain for the tedium of living.

Around 1974 I was a member of a group of writers and artists that included John F Deane and Henry Sharpe. We set up a publishing enterprise called Profile Press, and in the following few years published a number of books. For most of the year 1975 we also had a weekly session of readings and music in the Pembroke Bar. Many and varied were the talents that gravitated towards the Pembroke. One of the most unusual and most exciting was Michael Phillips.

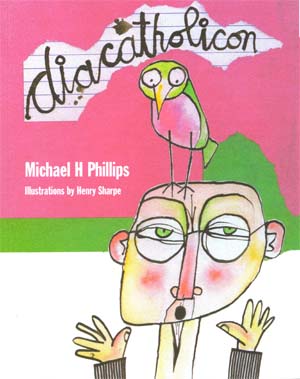

It was not just the handful of stories we published that distinguished him. He was also a talented musician and regularly provided some of the musical element of the Pembroke sessions. I knew him well. We were close friends, both working as teachers in the same school. Most of his stories that we published were accompanied by illustrations from Henry Sharpe. Sharpe appreciated the wicked humour in Phillips’s stories and the graphics complemented them con brio.

No wonder my friends were keen to track down these stories and their author – their wish to have Sharpe illustrate the stories anew. I was able to confirm that there were more stories than had been published. I had read several others and a substantial chunk of a novel. The excitement and anticipation were seismic.

The problem was that Michael Phillips had disappeared off the radar screen shortly after those stories were published, shortly after his virtuoso performances in the Pembroke.

He gave up teaching to try his hand at busking, with a view to travel. I remember one night in the Pembroke, after the gig, after the ensuing few jars, he asked me to drop off his large tape-recorder at his house, as he wanted to sleep in a phone box to harden himself up for the trials ahead. He became a regular feature at the entrance to the Grafton Arcade where he set up his music stand and played Baroque music on old-world recorders. Some of the resident winos didn’t like his style and started giving him grief, but the resident skinheads took to him, loved the music, and provided protection against all-comers. At one stage I had to extricate him from police custody, when part of our old school was burnt down, and he was arrested as prime suspect on the grounds that he must be unbalanced to have given up a permanent pensionable job to go busking. When I assured them he was perfectly sane and was not an arsonist, just pursuing a career change, they released him, but with heavy stares as if they were questioning my sanity too.

Sometime later he disappeared out of Dublin. Early reports were that he was seen in London, busking on the Underground. Occasionally he returned on his Russian Army motorbike with the side-car, and was spotted driving conspicuously around Dublin. Usually by the time I tracked him down with a view to a drink, he had already flown the coop again.

But sometimes he did call, and I got cryptic accounts of his escapades in various places, but particularly in London and Paris. He professed not to like Paris, nor the Parisians, to have resisted learning any more French than was necessary to order food and drink. Yet it was in Paris he spent most of the time in the years that followed.

In 1989 I found myself in Paris as the Bicentenary Celebrations of the Revolution were in full swing, and I looked him up. He, and his then partner, Karen, a former ballet dancer, had an apartment overlooking the Seine. Again he was dismissive of the charms of the city, but said he reckoned it was possible to drink 24 hours continuously. I challenged him that this theory should be put to the test straight away.

So we set out at six o’clock in the evening, starting leisurely with the local bars and cafes, making our way to the Square of the Irishmen, moving from one bar to the other as each shut down for the night. We then moved on and I remember we settled in to a cellar bar where they were playing jazz and we were befriended by a man who professed to being a ‘Breton Nationalist’ when he heard we were from Ireland. A few drinks later, when Michael began to suspect that our ‘Breton Nationalist’ was a Paris policeman, we made a hasty retreat out of the cellar. The red-light district of Boulevard St Denis was in full swing when we reached it, but we had to concentrate on our mission. When a beautiful black girl befriended Michael we had company for a while. I had not a word of French, but when I detected that she was offering a menu of delights, I reminded him of our mission. In the grey hours around dawn we were in the markets area where service was being provided for the early workers, then in the bar of a bus depot. I remember those shivering drinks, when we were reduced to sipping the smallest measures, and ordered them as ‘deux pression’, with a grim smile. However by nine or ten the regular street cafes were spreading out their tables and chairs and we were on the home straight, the 24 hour pub-crawl in the bag.

I didn’t see him again until I spotted him a few years ago on the streets of Dublin. He had returned, minus his Russian Army motorbike, his body and his health racked from excess. He was now turning a shilling as a graphic artist, the spirit restless to the last.

So when I took my friends to see him and to enquire about his writings, he laughed, as if he scarcely knew what we were talking about, as if it was too long ago, and he could no longer recall his previous existence as a writer. However we persevered, jogging his memory by mentioning the stories that had been published. Where were they now? And where was the novel he had started? He smiled enigmatically. Did he learn that from gazing at the Mona Lisa?

We met again, in one of the sawdust pubs he always insisted on, but which were getting very rare in opulent Dublin. He shook his head. He had looked around. Nothing. He remembered taking the manuscripts with him when he left Dublin, with the intention of working on them when he settled abroad. But he had never settled, and had never added a word to his opus or rather his opera.

So where did he leave them? In a phone box? Could well have – and he smiled wryly. But he was warming to the enthusiasm of my friends and promised to do his best to trace them.

The next night he brought a few type-written pages, yellowed, dog-eared, with circular stains of tea-cups or beer glasses, with multitudinous pen-marks, corrections, and amendments, obviously from the time they were typed. A thorough search had produced these, but that was all. However, he also produced a list of addresses some of the places he had stayed in London and Paris. He didn’t want to re-visit his past himself, but had no objection to my raking the debris to see what I could find. I looked at the list. The names were all of women. A big asterisk opposite some of the names indicated that those women were now dead.

I set to work, phoning or writing to the listed seraglio, some of whom I knew personally or by reputation.. And the past did start yielding up its riches. A story here, a fragment there, an old envelope with type-script pages from somewhere else.

Michael indicated he would be quite satisfied if the lot were burned, yet yielded to our enthusiasm for assembling the stories. When we invited Henry Sharpe to do new illustrations for them, and when Sharpe agreed with gleeful enthusiasm, it was settled.

As Michael was unwilling to re-work the material, there was a quandary. Some of the pieces were complete stories, but others were clearly fragments, others were sketches, or perhaps treatments for projected stories. Stories I had read all those years ago were not there, now obviously lost during a life wandering in search of casual experience. Eventually it was decided to publish all that had been unearthed, exactly as they had been found, letting the reader enjoy them for what they were.

|